The Devastating Disconnect: Why You Feel Like an Outsider in Your Child’s World (And How to Infiltrate)

Key Takeaways:

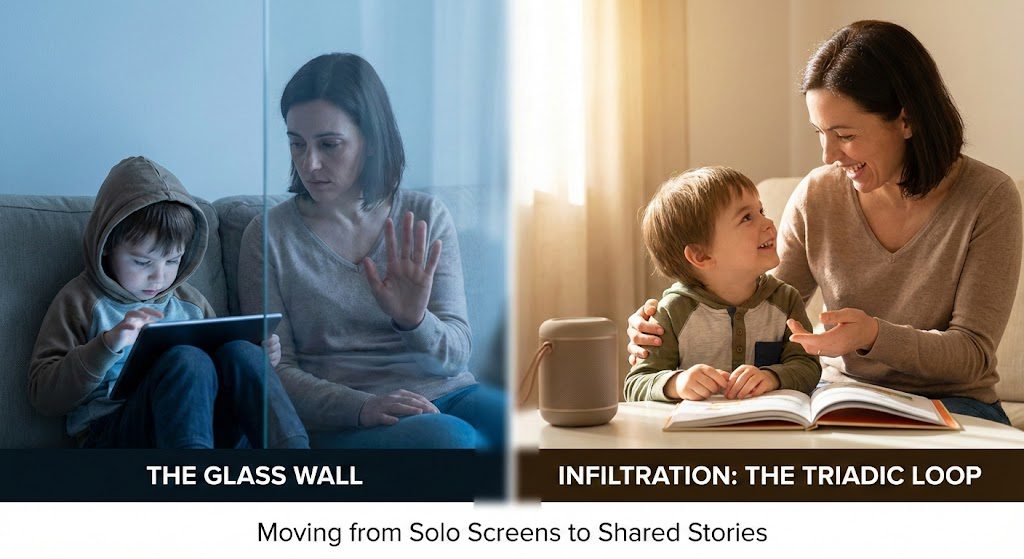

- The “Glass Wall” is Real: If you feel ignored, it’s likely a lack of “Joint Attention,” not a lack of love.

- Screens are “Solo” Silos: Passive screen time trains the brain for isolation; connection requires a “Triadic” loop (You + Child + Story).

- The Fix is Audio: Removing the visual screen frees up their eyes to look at you, rebuilding the neural bridge of connection.

The Hook: Tapping on the Glass

Do you ever feel like a ghostly observer in your own home?

You buy the toys they beg for. You put on the shows they love. You sit right next to them on the couch. But you feel… invisible.

You ask, “Is that a cool dinosaur?” They don’t look up. They just grunt.

It feels like they are trapped in a glass box. You can see them, and you can love them, but you can’t reach them.

For parents of neurotypical kids (our “Vitamin” parents), this is annoying. It feels like “kids these days.” For parents of neurodivergent kids (our “Painkiller” parents), this is devastating. It feels like a rejection.

But here is the good news: This isn’t a personality flaw. It’s a mechanic. And we can hack it.

The Science: The “Joint Attention” Circuit

To understand why you feel disconnected, we have to look at a concept in neuroscience called Joint Attention.

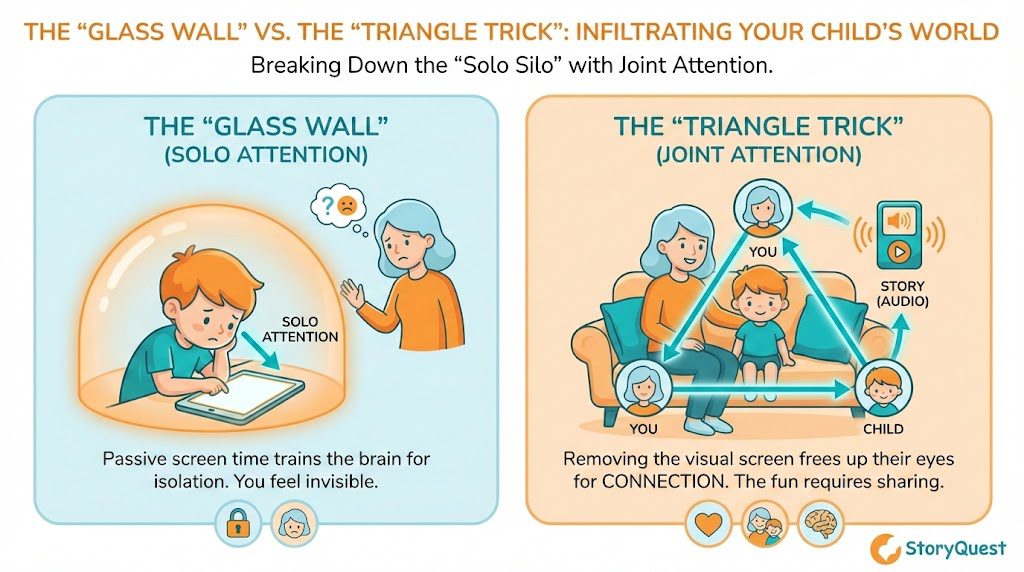

Most screen time today creates Solo Attention. The child’s brain is locked in a direct line with the device. The rest of the world (including you) fades into background static.

Joint Attention is different. It is the ability to share a common focus on something (an object, a story, a toy) with another person simultaneously. It is the “Triadic” Triangle:

- Child looks at Object.

- Child looks at You (“Did you see that?”).

- Child looks back at Object.

Why this matters: According to research published in Child Development, Joint Attention isn’t just “nice”—it is the fundamental building block of language acquisition and social cognition. It is how humans download culture.

When a child is glued to a screen, that “Triangle” collapses into a line. The “You” part of the equation is deleted. Recent studies have even shown that toddlers who engage in high levels of solo screen time show reduced initiation of joint attention behaviors later on.

You feel like an outsider because, neurologically speaking, you are.

The Dual-Benefit: Why We All Need This Hack

We designed StoryQuest to force this circuit back open. But the benefit hits differently depending on your child.

1. The “Vitamin” Parent (The Connection Seeker)

You want “Core Memories.” You want that warm-fuzzy feeling of laughing together at a joke.

- The Win: By moving the story from a screen (visual) to audio (aural), we free up their eyes. Suddenly, when the dragon roars, they look at YOU to gauge safety. That eye contact? That’s the dopamine hit of connection you’ve been starving for.

2. The “Painkiller” Parent (The Therapy Warrior)

If your child has ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) or a speech delay, your therapist has probably used the words “Joint Attention” a thousand times. It is often the #1 therapy goal.

- The Win: “Forced” eye contact creates anxiety. Shared eye contact creates safety. StoryQuest gamifies this. We make you the “Co-Pilot.” The child needs to check in with you to solve the riddle. It’s social skills training, but it feels like a heist movie.

Relevant Reading: Screen-Free Saturdays: Fun and Engaging Alternatives

Actionable Strategy: The “Triangle Trick”

You don’t need an app to start fixing this today. You just need to change your geometry.

The Old Way (Parallel Play): You sit next to them while they play/watch. You are both facing the same wall. This is low-connection.

The “Triangle Trick” (Triadic Play):

- Change the Angle: Sit so you are slightly facing them, not just parallel.

- The Interruption: If they are watching a show, pause it every 5 minutes.

- The Anchor: Don’t ask “What is happening?” (Test). Ask “Whoa, look at that [Specific Thing]!” pointing to the screen, then look at them.

- The Wait: Wait for their eyes to meet yours before you hit play again.

You are conditioning their brain to realize: The fun doesn’t happen unless I share it with Mom/Dad.

The StoryQuest Solution: The Digital Campfire

We built StoryQuest to automate the “Triangle Trick.”

Because there are no moving images to stare at, the child naturally looks for a visual anchor. That anchor is you.

- The Setup: You pick a hero (maybe “Captain [Child’s Name]”).

- The Hack: The AI narrator stops and says, “Captain, the door is locked! Ask your Co-Pilot (Mom/Dad) if we should use the Red Key or the Blue Key.”

- The Result: They have to turn to you. They have to speak to you. The “Glass Wall” shatters because the story cannot proceed without the connection.

It turns the “Device” into a “Campfire.” You aren’t staring at the fire; you’re staring at each other across it.

People Also Ask (FAQ)

Q: My child has Autism and avoids eye contact. Will this stress them out? A: Great question. Unlike “forced” eye contact (“Look at me when I’m talking!”), StoryQuest uses Referential Gaze. They are looking at you to solve a problem (the Red Key vs. Blue Key), which is much lower pressure. It shifts the focus from “social performance” to “mission success.”

Q: Is all screen time bad for connection? A: Not at all. The enemy is passive screen time (zombie mode). Co-viewing (watching together and talking about it) is actually beneficial. Research shows that when parents actively mediate media, it bridges the gap. We just make that mediation automatic.

Q: How is this different from just reading a book? A: Books are amazing! But let’s be real—sometimes you’re exhausted. StoryQuest does the heavy lifting of “telling” the story and generating the sound effects, so you can just relax and be the fun “Co-Pilot” rather than the tired narrator.

References:

- Mundy, P., & Gomes, A. (1998). Individual differences in joint attention skill development in the second year. Infant Behavior and Development.

- Study on Screen Habits and Attention: The effects of screen habits on attentional skills – NIH

Check also:

Strengthen Your Bond: Storytelling with Your Child

The 20-Minute Monologue: Why Your Child Talks AT You, Not WITH You